Hybrid is Dead

Long live flexibility!

Today’s newsletter is a BEAST: Nearly 2,000 words, tons of charts and insights.

If you like what you read, please subscribe, and share!

As we near the six year anniversary of the pandemic-created shift towards more remote work, it’s a good time for a data-driven assessment of the state of workplace flexibility. Who better to have a conversation with than Stanford professor Nick Bloom?

Stanford professor Nick Bloom

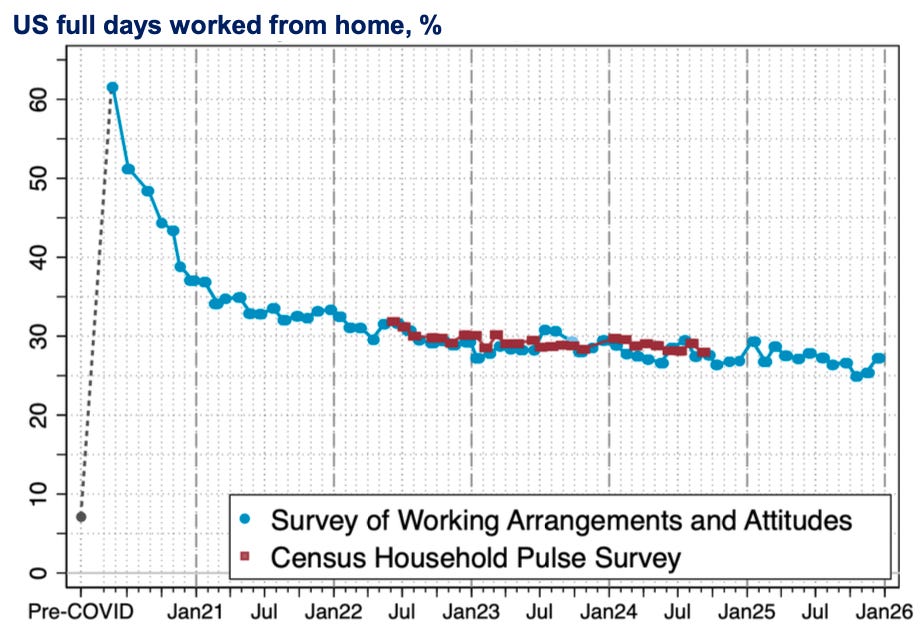

The headlines in 2025 were filled with stories of the “massive return to office,” but the data tells a different story. Work from home has stabilized at 25% of days in the US, nearly four times pre-pandemic levels. The actual shift in 2025? Average office utilization increased by 2-3 percentage points. That’s it.

“We are permanently seeing much higher levels of work from home. We are never going back to 2019,” Nick told the gathering. “There was a bit of a return to office move in 2024, but it’s not massive.”

Let’s skip past pontifications and clickbait and get into the data and dialog. Nick joined a Charter Forum session to share his latest data—some of it being published here for the first time–with a wide range of leaders.

The questions leaders asked, problems they raised and conversations were equally insightful: companies are largely past arguments about policies and wrestling bigger challenges around how large-scale organizations remain engaged, nimble and effective in a digitally-enabled, distributed world.

Stability is boring (but true)

Having spent nearly 6 years building data sets and collecting research in this space, the main story of the past few years is a lot of CEO pronouncements and slow, modest changes in reality.

Work from home has plateaued at 25% of days in the US (3.8X pre-pandemic levels), with 71% of even the Fortune 100 companies adopting flexible policies. Shifts, even quarter to quarter, are quite small regardless of headlines.

Source: Stanford SWAA, except this is a pre-release view into December ‘25!

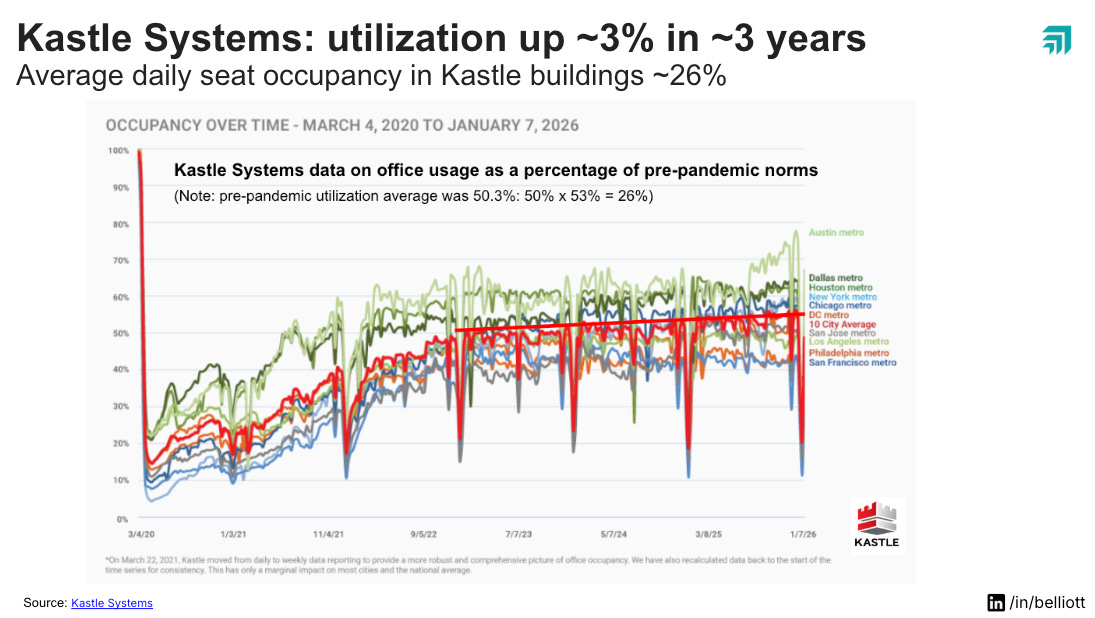

Data from Kastle Systems and Placer.ai show the same thing: while headlines all proclaimed a massive return to office in 2025, the average increase in office utilization was probably an incremental 2-3 percentage points on average.

Source: Kastle Systems “Return to Work Barometer” (please, that name…it’s been 6 years!)

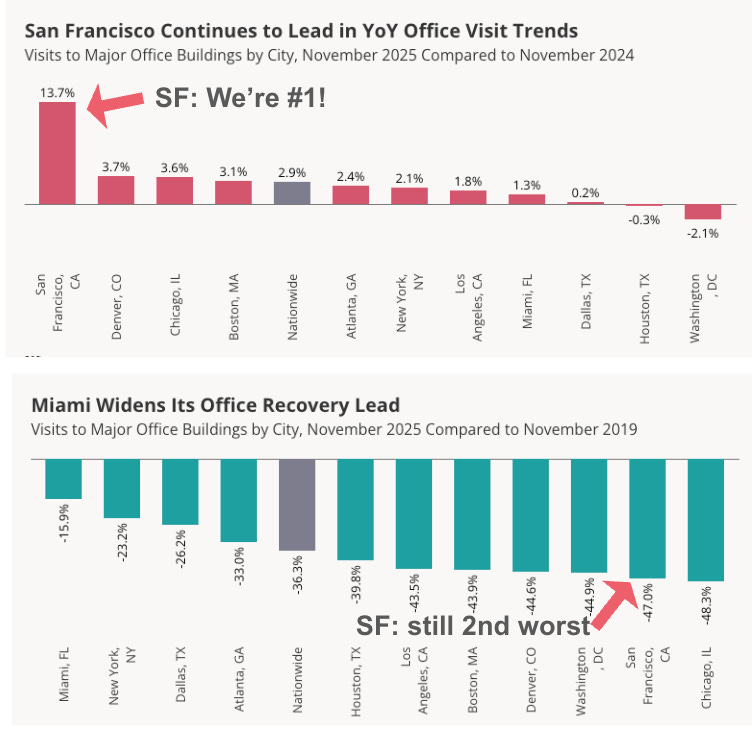

Markets like New York and San Francisco SF have seen more RTO traffic. Fortunately, office traffic in San Francisco grew the most of any major market, but SF is still the second worst major market in the US, behind only Chicago.

Source: Placer.ai, November 2025

Office market recovery is a good thing: broad financial stress from a commercial real estate collapse is a bad idea. But part of the recovery is that in 2025 the supply of office space in the US went down not up for the first time in 25 years.

Big company CEOs: Get in the office (or get out)

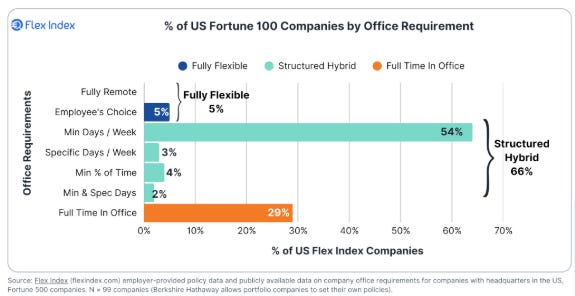

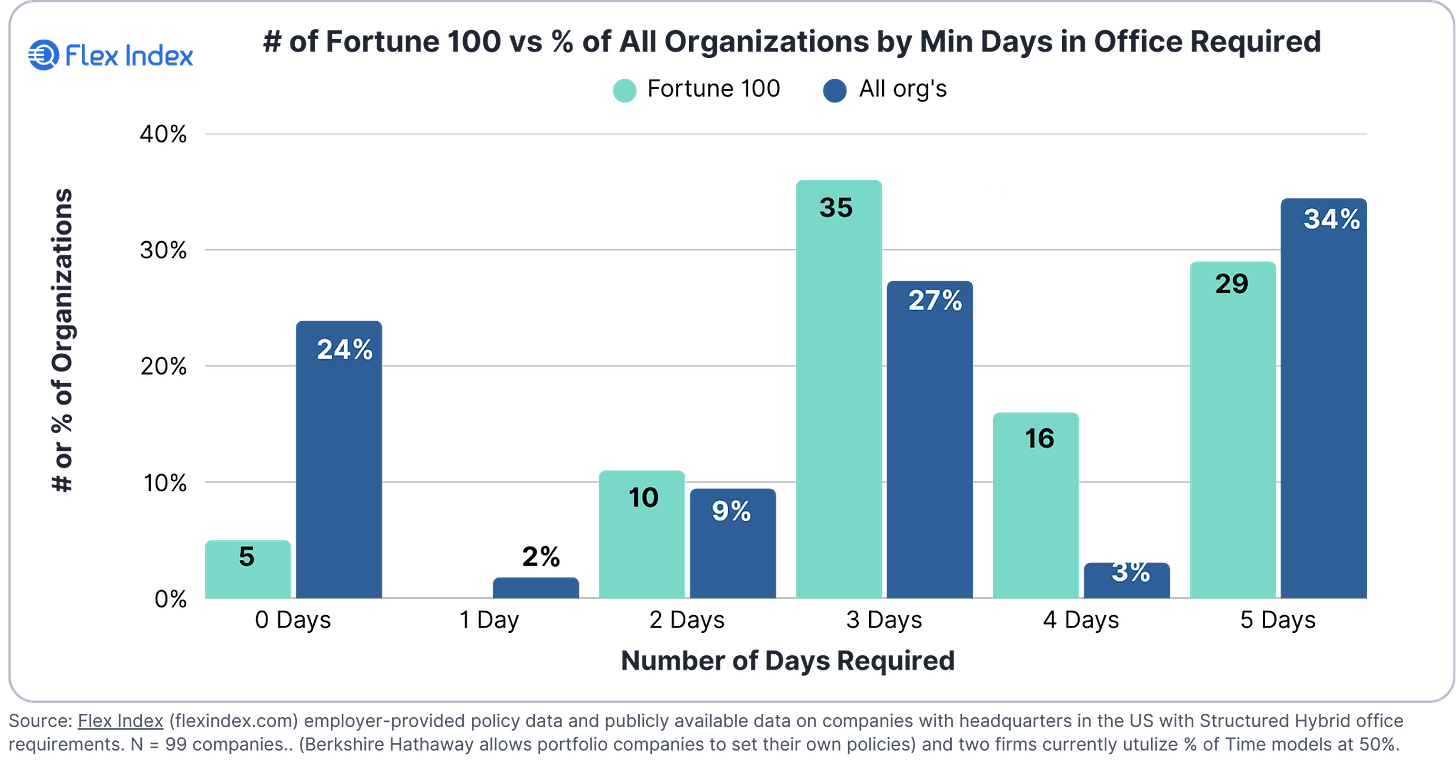

The loudest noise around RTO has come from the biggest companies. Among Fortune 100 companies, 72% have flexible workplace policies. Only 29% require five days in the office—companies like Amazon and Goldman Sachs that get all the media attention.

Source: Flex Index, Q3 2025

But the headlines are all RTO, every time.

“The media tends to love focusing on them, but they’re not the majority, they’re the minority,” Bloom said. “Particularly in tech, hybrid’s become kind of the default. Amazon is fully in-person. There are not many other tech firms trying to get people fully in-person.”

Even among the Fortune 100 (where we’ve seen the strongest RTO push) 71% have some form of flexibility. The difference? They’re more likely to demand four days a week. Why? It’s often tied to desires to drive voluntary attrition (as noted by the Federal Reserve) or, as one executive put it, “CEOs and their own egos.”

What this means for you: If your CEO is pressuring you to mandate four or five days because “everyone else is doing it,” show them the data. The companies getting headlines represent the minority approach, not the winning playbook.

Why hybrid won (hint: it’s economics)

The debate keeps circling back to culture and innovation, but the real driver is simpler: profitability.

Bloom’s Nature paper examined Trip.com’s randomized trial of 1,600 employees: half working hybrid (3 days in office), half fully in-person. The results after 24 months: zero performance difference, but quit rates dropped by a third for hybrid workers.

“They estimated it was saving them $20,000-$30,000 per employee and had no effect on revenue,” Bloom explained. “This is driven by market forces. Hybrid peers are just, to be honest, more profitable because it helps with retention.”

The math is straightforward: every person who quits costs roughly $50,000 to replace. Cut turnover by a third, you’ve found your business case.

As Nick, LSE Professor Prithwiraj Choudhury and I wrote in MIT Sloan Management Review last fall,

“To date, no peer-reviewed research shows a benefit to having a rigid five-day office model.”

The debate about “hybrid” tends to default to compliance: Are people falling in line? Leaders treat hybrid work as a policy challenge when the reality is that it’s a leadership capability challenge.

If you’re unwilling to put the effort into redesigning how people work to enable the modest flexibility that working 2 days a week from home requires, how do you keep a straight face while saying you’ll reimagine work with AI? At a minimum, you leave your employees asking: Are we part of the solution, or are people part of the problem you’d like to eliminate?

Related reading: Hybrid Work Is Not the Problem — Poor Leadership Is by me, Nick Bloom and Prithwiraj Choudhury in MIT Sloan Management Review

The gathering strategy boosts productivity 8%

New data alert! For companies worried about connection, Bloom shared new unpublished research that surprised even him: bringing fully remote workers together just one day per month cuts quit rates nearly in half and boosts productivity. He’s running a randomized control test with fully remote employees in a service sector firm.

“We randomly have one group come in for one day a month, and the other group remain fully remote. So group one comes in one day a month, and they work, have lunches and coffee breaks together. They spend that one day a month bonding.

What you find, interestingly, is their quit rates fall by almost a half. When you interview them, they say they like the connectivity. It’s not like they want to come in every day, but they don’t come in one day a month because they feel more connected up and it’s more sociable.

They also see their productivity rise by 8%, and it’s to do with reaching out. They just message each other more and slowly over time that group sees rising productivity.”

This aligns with LSE professor Raj Choudhury’s finding that roughly 25% in-person time—whether one day a week or one week a month—hits the sweet spot for distributed teams in terms of engagement, collaboration and quality of work.

What this means for you: If your teams are distributed, stop mandating arbitrary daily attendance. Invest in quarterly gatherings with real agendas and as much time for connection as strategy and goal alignment.

Related reading: Building Connection at Scale: Zillow shares their master’s class in how to build connection in distributed teams.

🔆 Special Offer 🔆

Want to hear Nick Bloom live? Join Charter’s Leading with AI Summit on Feb 24th in SF to hear from Nick, along with Donna Morris (Walmart), Amjad Masad (Replit), Hannah Prichett (Anthropic),Fiona Tan (Wayfair), Rani Johnson (Workday), Aneesh Raman, Jessica Lessin, Helen Kupp and Charter Forum members Brandon Sammut (Zapier) and Iain Roberts (Airbnb)! p.s. NYC on Feb 10th is just as good.

50% off in-person registration (pending approval) with the code FORUM!

Anyone can register—for free—for the virtual sessions.

The monitoring trap

Some companies got more sophisticated at tracking attendance, combining badge swipes, WiFi logins, sick leave data, and travel records. Others put their energy into more productive endeavors.

Here’s the paradox: as tracking improves and that gap narrows, you’re not creating value, you’re creating resentment. Nothing says “I don’t trust you” like individual badge tracking, unless it’s badge tracking that also counts hours.

“It’s complex and burdensome and honestly often pointless,” one workplace leader observed. “The act of measuring and monitoring itself is maybe helpful if you’re making a case against an underperforming employee, but otherwise it’s just irritating.”

CBRE’s Emily Botello told me many companies who enforced three-day policies a year ago have quietly stopped, “wary of the burnout that comes from turning professionals into attendance monitors.”

As an aside, I bet there are Amazon employees out there in private forums proudly declaring their “zero badger” status and testing how long they can stick it out. A hugely productive use of time.

Solutions. Before investing in better tracking systems, ask whether compliance is actually your problem. If people are delivering results, monitoring becomes theater. If they’re not delivering, showing up won’t fix it.

Productivity isn’t 9-to-5

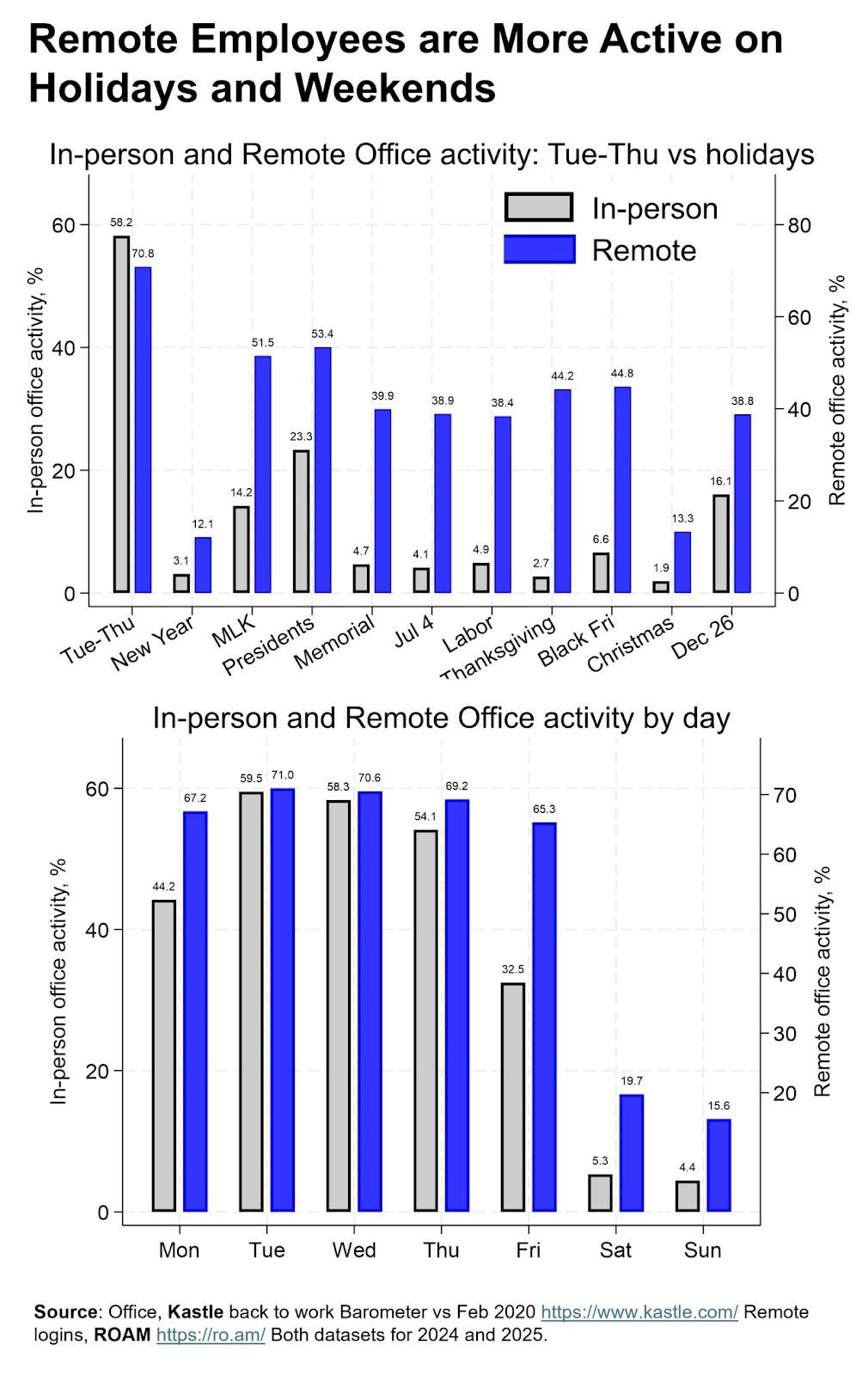

One of the biggest problems with monitoring offices: it’s not the only place people get work done. Microsoft talks about the infinite workday. Remote workers spread their hours across evenings and weekends far more than office workers.

“You may go to the dentist that day or pick your kid up from school and make up for it another day or the weekend,” he explained. “You shouldn’t be evaluating people on their work in just one day.”

Bloom’s comparison of remote work platform data with office badge swipes shows this: remote workers span into the weekends and across holidays, for good and ill.

That spread also creates coordination challenges when teams mix remote and in-office workers: who’s available when to meet? That problem is even more challenging for teams spread across time zones.

Solutions. Establish core collaboration hours: periods when everyone’s expected to be available regardless of location for meetings, calls and quick chats. One approach: 9am-1pm in your primary timezone, Monday-Thursday. Outside those hours, let people work when they’re most effective.

Two real challenges worth watching

The authenticity problem. Recruiting impersonations, AI bots and more are creating new security concerns for remote work.

“If someone’s there in person, you can tell it’s a real person. Whereas if they’re fully remote, you’re never sure who you’re dealing with,” Bloom noted.

Companies are already shifting back to in-person final interviews. Smart organizations are pairing this with regular in-person gatherings and camera-on norms for critical meetings.

Hybrid meetings (still) suck. The real problem isn’t just too many meetings, it’s that we’ve made quick conversations impossible. Virtual office tools like Roam promise easy audio-only connections, solving what Bloom calls the “30-minute Zoom problem”:

“I don’t want to talk to you for 30 minutes, you want to talk to me for two minutes, and so this is like peering over the cubicle wall.”

But Slack and Teams already do this. The barrier isn’t the tool, it’s that nobody’s set norms making it okay to just call someone. If 40% of teams are distributed across cities (CBRE data), making every meeting a hybrid meeting.

Solutions. The problem isn’t tools, it’s leadership. Train managers to normalize quick audio calls for simple issues. Model the practice yourself! For hybrid meetings, my team at Google created two rules:

Assign a “hybrid moderator” in the room to monitor chat and make sure people dialing in can hear and be heard.

“Zoom wins:” if someone dialing in has something to say, they go next (otherwise room dwellers dominate).

If my team at Google in 2016 could do it, so can you.

Why “hybrid” is dying

You might notice I’ve said “flexibility” much more than “hybrid” in this piece. That’s deliberate.

“The term is dying,” Bloom said, noting he removed it from his work-from-home book title. “It wasn’t a term before the pandemic.”

The problem isn’t just linguistic. “Hybrid” focuses on where people work when the real questions are how teams collaborate, why they gather, and when presence actually matters. It’s a binary category trying to describe something deeply nuanced. It’s why I’ve hated the term since 2021.

As Bloom put it:

“You don’t want to be either fully remote all the time or fully in-person all the time. There’s some kind of balance in the middle, but it’s complicated.”

The companies figuring this out have moved past policy debates to capability building. They’re quietly racking up advantages while everyone else argues about badge swipes.

What’s your biggest learning from the past six years?

Brilliant reframe on moving from policy compliance to capability building. That Trip.com data about turnover dropping by athird really cuts through the noise. I've seen teams struggle with rigid badge tracking when the actual issue was unclear deliverables, kinda like using a hammer on a screw.

The framing that hybrid works because of cost savings from reduced attrition is (at least at surface level) contradictory with the point that many CEOs are using RTO policies as a way to increase desired attrition. It seems like the nuance is in how Hybrid can balance driving non-regrettable attrition, while minimizing regrettable attrition.