Stop Ranking People, Start Lifting Performance

Research shows stack ranking kills collaboration — here's what really works

Over the past few months, we’ve seen the return of “rank and yank” performance reviews: stacked ranking systems at companies like Meta where managers are now being told to grade 15-20% of employees as below expectations. Just the other week Amazon doubled down as well, announcing a new performance review system that formally embeds "Leadership Principles" as a core metric, with only 5% of employees eligible for the top rating and fixed percentages for each performance tier.

At the same time, successful CEOs like NVIDIA’s Jensen Huang and Airbnb’s Brian Chesky have led the wave of conversations about walking away from one-on-ones with their reports, opting instead for larger group sessions for shared context and learning.

Both of those systems of management might work in the short term, or for people in the C-suite, but history says that long term the results will be a loss of engagement, increased internal competition and higher voluntary turnover among top performers.

But too often leaders struggle to find alternatives. Last month, I spoke with a senior executive who said, "We keep saying we want to get rid of the annual performance appraisal process, but no one's ever come up with an alternative."

Really? That we’re that stuck with “this is the way”?

In search of better answers, I turned to Ashley Goodall who has been proving there's a better way for over a decade, and now consults on this and other leadership topics with a range of global leaders. At Deloitte, he led the transformation of performance management for 75,000 people. At Cisco, he scaled it globally. The results weren't just better employee satisfaction – they were measurably better business outcomes.

Ashley Goodall, author of Nine Lies about Work and The Problem with Change

Rank and Yank: a Brief History (and Consequences)

Meta and Amazon’s moves are particularly puzzling given that companies like Microsoft and GE abandoned similar approaches after years of documented damage to innovation and teamwork.

I’ve been around long enough to remember General Electric CEO Jack Welch’s 70/20/10 “vitality curve”: 20% of the organization are your “A” players, 70% are “adequate” and the bottom 10% just need to go. Microsoft, primarily under Steve Ballmer’s tenure as CEO, followed suit in the 2000s.

There have been enough studies done on those organizations and others to show the challenges. There are short term productivity gains (taking out headcount) and early surveys inside GE reported clearer performance expectations. Those short term gains were followed by long term pain: lowered trust and higher voluntary turnover among top-quartile performers.

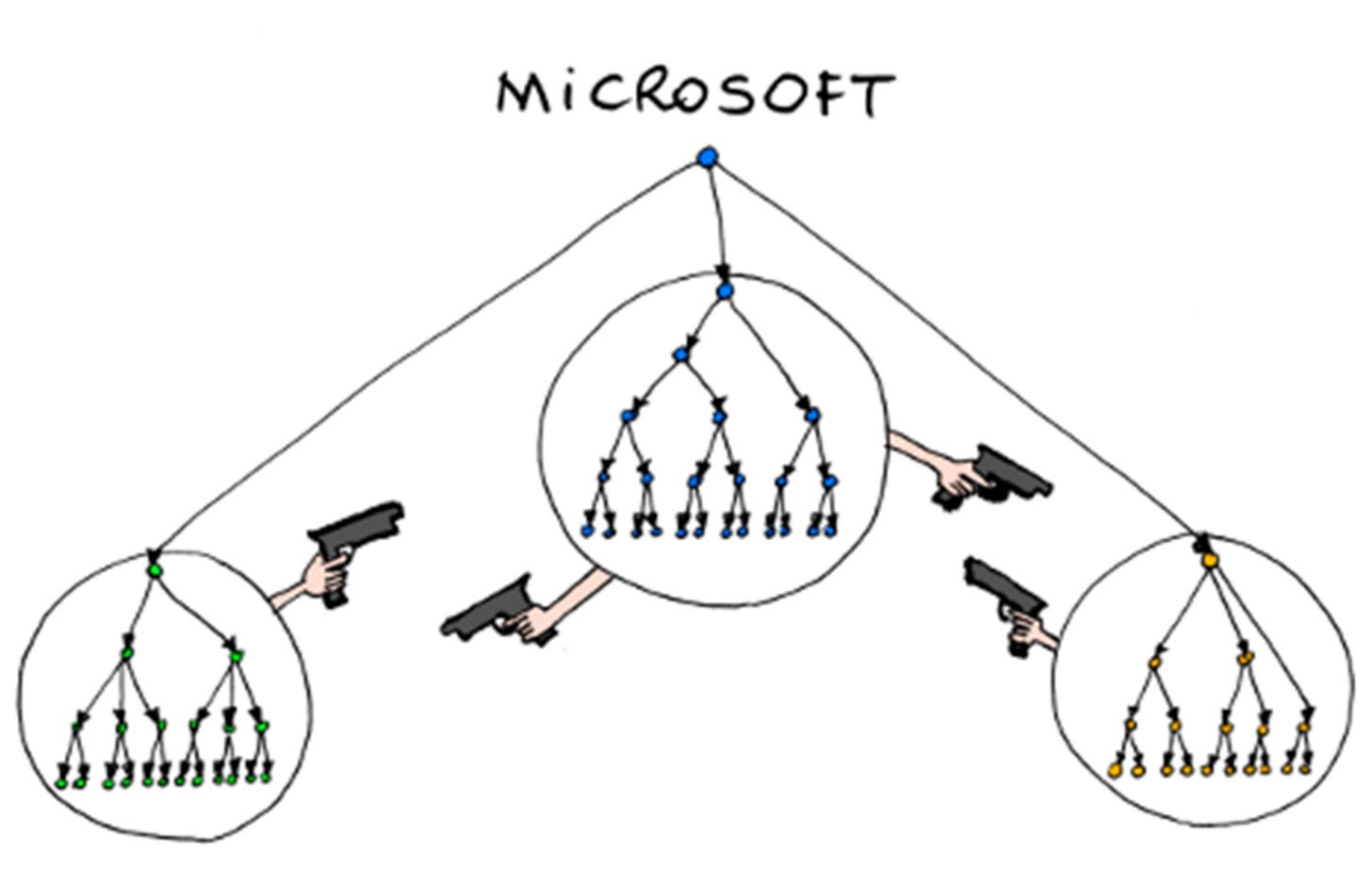

Stack ranking coincided with Microsoft’s “lost decade”: OS/Office profit engine held, but share in mobile, search, social and cloud lagged peers; many analysts cite the system as inhibiting cross-team innovation — to the degree it became a public example of internal strife:

After abolition in FY14, engagement and voluntary attrition metrics improved within two cycles – aka the end of the Ballmer era.

Microsoft’s Org Chart, source: Bonkers World

The Fatal Flaw in Annual Reviews

Traditional performance management has it backwards. "It's designed to sort people, not help them," Goodall told me. "There is not a single thought in traditional performance management that is there to help employee performance improve."

The numbers back this up. In Goodall’s report on the changes at Deloitte for Harvard Business Review, they found that creating ratings consumed close to 2 million hours annually — time that could have been spent actually helping people do their work more effectively.

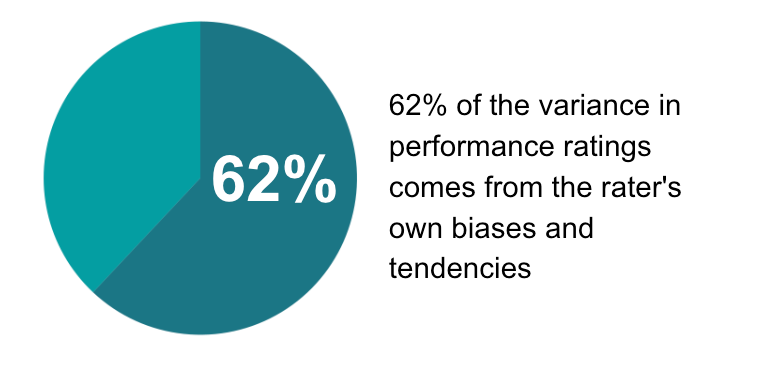

Even worse, the research shows that 62% of the variance in performance ratings comes from the rater's own biases and tendencies, not actual performance. "Ratings reveal more about the rater than they do about the ratee," as Goodall puts it.

Source: Reinventing Performance Management, Marcus Buckingham & Ashley Goodall, AAPL Nov 2024

At Cisco, he witnessed many of the same dysfunctions: "Most rating systems do a mediocre job of making performance visible because they begin by saying ‘here is the required distribution of performance.’ And then you go, great, how many middle performers do we have? The answer comes back, ‘Well, the system says 60%.’ Did you measure that?, you ask. ‘No, we decided that's how many we had.’"

As one former Microsoft employee described their old system: "If you were on a team of 10 people, you walked in the first day knowing that, no matter how good everyone was, two people were going to get a great review, seven were going to get mediocre reviews, and one was going to get a terrible review.”

That in turn leads to employees focusing on competing with each other rather than competing with other companies.

The result? Biased annual (or even biannual) processes that are forced onto a curve. A system that creates internal competition, undermines collaboration, and fails at its most basic job: helping people get better at their work.

Separating Performance from Pay

One of Goodall's key insights was the need to separate performance conversations from compensation decisions entirely. At Cisco, they eliminated the elaborate rating systems and simply gave team leaders budget authority for compensation decisions. "You have a budget. You give the budget to the team leader. You tell them to hand out money. And most team leaders say ‘Yes, I do have a point of view on these people.’ We denominate pay in dollars, everybody understands why. We don't need to denominate performance in ratings." Goodall explains.

This approach eliminates the artificial scarcity that makes ratings feel unfair. "Compensation dollars are zero sum in a given organization, whereas ratings just pretend to be zero sum, and the pretendness gets people all annoyed. ‘We ran out of dollars for your bonus,’ is much easier to stomach than ‘we ran out of ratings for your performance.’”

The Weekly Check-in Works

With compensation handled separately, Goodall could focus on what actually drives performance: regular, supportive conversations between managers and their people.

The data from Cisco was striking. Monthly manager to employee conversations had a negative effect on team engagement.

"What happened was that somebody showed up and said ‘this half hour is all about you.’ The employee shares what’s working, what’s not, what they need. And the leader says ‘We'll do those things. Great chat.’ And then vanishes.” The reaction from there? “‘Oh, so you could actually be a good leader for me – you just can't be bothered to do it more than once a month.’"

Every three weeks was neutral. Every two weeks showed positive results. But weekly check-ins? "Every week was a huge bump, a 13 to 16% boost in team engagement—numbers you would bribe people for in your annual engagement survey."

These aren't performance reviews in miniature. They're coaching conversations built around four simple questions:

What help do you need from me?

What are your priorities for next week?

What did you love about last week?

What did you loathe about last week?

"The weekly conversation isn't feedback, it's attention," Goodall emphasizes. "What help do you need from me? Where are you stuck?"

What Makes Check-ins Actually Work

The magic isn't just in frequency: it's in predictability and employee ownership. "This is the last meeting you cancel in the week or you reschedule. It needs to have an element of predictability because people plan for them."

Employees can save issues for their check-in rather than creating urgency throughout the week. "Team members will go through the week and keep track of what they want to talk about, bring it to the check-in, which removes all sorts of swirl in the week."

Crucially, these conversations are on the employee's terms. "It's got to be on the employee's terms. They set the agenda. So it's not the leader reading a list of to-do items. It's an upwards conversation, not a downwards conversation. So it embodies agency and it embodies trust."

The business results followed the engagement gains. At Cisco, teams with weekly check-ins showed better sales goal attainment and higher quality scores from clients.

The Leadership Commitment Required

This approach demands more from managers, not less. As Goodall puts it: "For us, these check-ins are not in addition to the work of a team leader; they are the work of a team leader."

The payoff comes from creating managers who are "trained and adept at helping you do your work. And the result of that is organizational performance."

At Cisco, even CEO Chuck Robbins was an early adopter, conducting weekly check-ins with his direct reports. "He would tell everybody about it. And his team would say he does – every week."

So, are Jensen Huang and Brian Chesky wrong when it comes to ditching their 1:1s? They might be absolutely fine: they’re working with seasoned, experienced professionals. But that misses out on factors like ensuring alignment and key differences like leaders who are newer to the organization.

Regardless, just one or two layers down in their organization are people who are still learning the ropes, need support and development help on a more continuous basis.

Better Alternatives (That Actually Work)

Just saying "ditch ratings systems" isn't enough – leaders need practical frameworks that actually improve performance. The good news? Several organizations have cracked the code.

Netflix's "Daily Brushing" Approach: Netflix pairs annual 360-degree feedback with a culture of continuous, honest conversations. As former Netflix Product leader Angela Morgenstern told me, "The annual 360 moment is like going to the dentist. You need a formal check-in and be forced to look at the state of your cavities. But you also should be brushing your teeth every day."

The magic is in normalizing real-time feedback rather than saving everything for an annual dump of criticism and praise.

Deloitte's Future-Focused Questions: Instead of backward-looking ratings, Deloitte switched to four simple, forward-looking questions that managers answer about each team member:

Given what I know of this person's performance, would I award them the highest possible compensation increase?

Would I always want this person on my team?

Is this person at risk for low performance?

Is this person ready for a promotion today?

These questions force managers to think about actual business decisions rather than abstract ratings. They also require deeper thinking than gut feel.

Flexible Check-in Models: Weekly face-to-face isn't the only path to success. Goodall found that asynchronous check-ins – the same four questions answered digitally – still showed positive engagement effects, just smaller ones. At Slack, my team used "agenda channels" to park discussion items between our regular meetings, creating ongoing dialogue without constant interruptions.

The key is consistency and employee ownership, whether that's weekly video calls, biweekly coffee chats, or structured digital exchanges.

Start Today

The most compelling aspect of Goodall's approach is how achievable it is. You don't need to overhaul your entire HR system overnight. You can start with a pilot group, measure engagement and performance outcomes, and scale what works.

"You just apply your dependent variable – engagement, productivity, or another outcome measure – to both groups and see what happens," he suggests, referring to running old and new systems in parallel. The Cisco example of looking at sales team performance is a classic place to start.

The choice is clear: continue investing millions of hours in systems that sort people into categories with arbitrary boundaries, or start having conversations that actually help them do better work.

Amazon's recent announcement is a cautionary tale: a major tech company returning to practices that Microsoft, GE, and others abandoned after years of proven damage. The research is clear: forced rankings and cultural assessments as performance metrics create exactly the opposite of what leaders want: less collaboration, reduced innovation, and higher turnover among top performers.

As Goodall told me, "Human psychology hasn't changed. We’re still wired the same way." Weekly attention, clear priorities, and genuine support aren't revolutionary concepts: they're basic human needs that traditional performance management has been systematically ignoring.

The revolution isn't about technology or new frameworks. It's about remembering that the goal isn't to measure performance – it's to lift it.

What's your experience with performance reviews? Are you pro or con weekly 1:1s? I'd love to hear your thoughts: leave a comment to start a conversation or reply to this email!

ICYMI

Your company will never love you back.

Your Megacorp may not even like you. Continual cuts are in vogue, regardless of decades of research showing layoffs don't pay off — short term inefficiencies, long term loss of engagement.

It's hard for people to learn new skills and invest in reinventing entire workflows if they feel like they could get cut at anytime. Fear and a lack of trust aren't exactly the recipe for successful change programs.

Molly Kinder at The Brookings Institution talked with Chip Cutter about the lack of worker power and pushback with the threat of AI coming for their jobs. The closer for me? “Something feels remarkably different about this moment.”

So say we all...this isn’t going to end well. Read on, and my post on LinkedIn.

“America is treating working people like shit.”

Is AI destroying entry-level jobs — and coming for the rest of white collar work?

Matt Stoller does a great job digging into broader trends to get at a less-panicked take, but still comes to the conclusion that AI will take jobs — because it's capital-friendly, certainly not labor-friendly.

The impacts are likely to be worse if there's a recession, which would of course deepen a recession. Doom loop, here we come.

"There is no real policy answer to 'AI is going to take our jobs,' because what that phrase really means is 'America is treating working people like shit.' And to fix that, well, we have to break our national addiction to higher returns on capital, and then do something like the New Deal again."

I'd suggest reading the whole thing, it's worth 15 minutes of your time.

I honestly do not understand what is so hard: if you care about people, they will care about you.

If you pet your dog, provide him with food and shelter and nice walks together, he will love you back.

Humans are not that different.

Talk to people regularly, listen to their concern, learn the name of their kids and what they like to do in their free time.

It is not about becoming friends, but only about caring about them as human beings.

And if you don’t care about people and don’t want to do the people-part of the work, why have you accepted a people management position in the first place?

I wonder if it is not simply an ego problem from leadership: you want to be seen as tough, hard, cold and unemotional - and so you tell this story to your buddies in the leadership circle and everybody fakes believing it.

Then when it doesn’t work you just add the chapter “the average person is just too soft and we need to accept his mediocrity” and you keep being the hero.

I wonder.

Both the Bell Curve and Power Law Curve are nonsensical when it comes to organisation performance. Yet they’re the two most commonly cited metrics.

Never seen anybody use actual Performance Curve data.